HISTORY

Soshichiro Nagatani discovers how to manufacture sencha green tea!

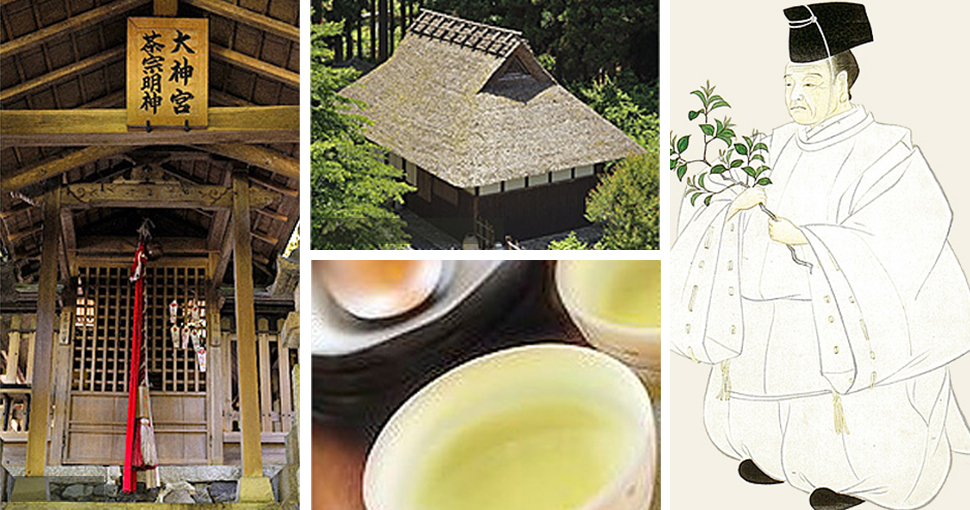

Nagatanien can trace its origins back to Soshichiro Nagatani, a manufacturer of tea in Ujitawara, Tsuzuki, Kyoto prefecture in the mid-Edo period, who later changed his name to Soen Nagatani when he entered the Buddhist priesthood. Soshichiro is a significant figure in the history of Japanese tea, best known for discovering how to produce sencha green tea.

The desire to create a better tasting tea

The eighth shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, Yoshimune Tokugawa , was ruling Japan. People used to drink a dark-red tea decoction, but its aroma was weak and it did not taste very good. Meanwhile, tea specialists, who made a living out of producing and manufacturing tea, maintained strict control over the sale of matcha green tea, putting it well beyond the reach of ordinary citizens. As a tea manufacturer, Soshichiro Nagatani felt an obligation to do something to help.

He determined to produce a tastier tea that regular folk would be happy to drink. After 15 years of much research and testing, Soshichiro finally came up with a manufacturing method for sencha green tea.

To date, the tea leaves for widely drunk tea decoction were made by picking not only young tea leaves but also those that are old, which were boiled in scum, squeezed and roughly kneaded before being dried by the sun and air.

By contrast, Soshichiro’s method involved picking only the year’s new tea leaves, which were then steamed and squeezed gently between the fingers while being dried on top of drying ovens. In other words, he managed to control the leaf browning by applying heat to inhibit enzyme activity, maintaining the green tea leaf color. The delicious tea made from the new leaves had a beautiful light green color with a balmy fragrance and a slight sweetness of taste. The tea’s attractive green color was so impressive compared to the previous tea decoction that it became known as seisei sencha or vibrant sencha green tea.

Spreading sencha green tea throughout Japan

Keen to spread knowledge of the new tea across the country, Soshichiro carried sencha green tea to the great city of Edo (old name of Tokyo) in search of new commercial opportunities. On the way, he climbed to the top of Mount Fuji, where he is said to have prayed, “Please help me spread this tea far and wide.”

Upon reaching Edo, Soshichiro took the sencha green tea to many tea sellers.

He was given a lukewarm reception by most tea sellers because it was so different from the current tea decoction. However, one tea seller in Nihonbashi, Kahei Yamamoto (current Yamamotoyama), recognized the value of the new tea.

Kahei Yamamoto started selling the tea under the name “tenkaichi” (best in the world), and it soon became a best-seller across Edo.

Soshichiro did not patent his new production method, but shared it freely with many people. Gradually, sencha green tea started to be produced all over the country.

By the end of the Edo period, it had become one of Japan’s two main exports to the United States and many countries in Europe and as popular as raw silk thread.

Soshichiro died in 1778 at the age of 98.

The story of Soshichiro’s great endeavors was passed down through the generations, and he was enshrined as Chaso Myojin, the god of tea, in his birthplace of Ujitawara, Kyoto. Today, many people in the tea industry still come to pray and show gratitude to Chaso Myojin.

Soshichiro’s prayer on the peak of Mount Fuji to “spread this tea far and wide” has been granted, with sencha green tea transcending time and place to reach many, many people.

The story behind the best seller, Ochazuke Nori, green tea seasoning for rice soup!

Nagatanien’s hit product, Ochazuke Nori was launched in 1952.

What is the story behind this great success? We dug deep into the history of the product and found out some undiscovered truths.

The beginnings of Ochazuke Nori

Yoshio Nagatani, who established Nagatanien Honpo Co., Ltd. in 1953, was a member of the time-honored tea merchant family descended from Soshichro Nagatani, the creator of Japanese sencha.

Yoshio’s father, the ninth-generation manager of the Nagatanien tea store, was not only involved in the making of tea but in the development and retail of new products. One of those products was Nori Seaweed Tea. The product was made by finely cut seaweed, mixied with matcha tea powder and salt, and add hot water to drink. It was a type of mix of clear soup with nori seaweed topping. After World War II, this Nori Seaweed Tea was improved and relaunched as Ochazuke Nori (green tea seasoning for rice soup).

Ochazuke Nori was made entirely by hand, primarily from powdered seasoning, finely chopped nori seaweed, and crispy rice crackers. In those days, there were no aluminum foil or polyethylene. To prevent the seaweed from becoming damp and limp, it was sealed in a double bag and then put into jars of 100 bags each on a bed of caustic lime.

The company decided on the simple name of Ochazuke Nori, the words of “green tea rice soup with seaweed” in Japanese as they are. But it was not as simple as it seems, with careful and detailed thought going into the font design to express the traditional atmosphere associated with ochazuke. As for the package design, a yellow, red, black, and green striped pattern was chosen in the style of a curtain of kabuki, Japanese traditional theater.

A rocky road to star product status

In the early days, the product was delivered door to door in a cart attached to the back of a bicycle. The colorful packaging also caught people’s attention in the store, turning the product into an unexpected hit. The product was then delivered to department stores through the wholesaler. The store held demonstrations to introduce this completely new product and worked hard to spread awareness, all of which helped generate strong sales.

However, the orders from department stores ceased abruptly after competitors noted the product’s popularity and started producing copycat items. The product packaging at the time was printed with the words “The flavor of Edo – Ochazuke Nori,” so the company couldn’t complain when similar products started to circulate. It taught Yoshio the importance of branding and he immediately reprinted the product packaging to include the Nagatanien label, and subsequently worked tirelessly to establish the Nagatanien brand.

Despite the many trials and tribulations, sales of Ochazuke Nori expanded favorably and the product grew into a nationwide best seller.

Achieve that exclusive matsutake taste, quickly and easily

It was October 1964. The mood across Japan was sparked by the excitement of the Tokyo Olympics. Nagatanien was developing its long-term best-selling matsutake-flavored clear soup mix.

The days of trials and errors

The most important element in creating the matsutake-flavored clear soup was to get the balance of flavor exactly right. According to the head of research, that involved carefully selecting the raw ingredients and distinguishing each individual seasoning. If something didn’t taste right, it was singled out and removed. It was a painstaking, diligent process.

The team tasted the soup 10 to 20 times a day. They had kept repeating trials and errors on matsutake to the extent that they almost got tired of the coveted luxury taste of it.

The biggest hurdle was the manufacturing of the seasoning granules that served as the taste base. This involved processing salt, sugar, essences, and other ingredients into granular form. However, the granules were completely different depending on how the ingredients were blended and mixed. Either they didn’t form proper granules, or the granules were too hard to dissolve properly in boiling water. The process was adjusted countless times before achieving successful method.

Penetrate the market with suggested recipes

When launching the matsutake-flavored clear soup, there was much debate within the company about how to market the product. Consumers in Western Japan were already familiar with the concept of clear soup thanks to the indigenous sumashi clear soup. However, consumers in Eastern Japan mainly ate miso soup as opposed to clear soup. We decided to use TV commercials to suggest various ways of using the flavoring, including adding mochi rice cakes and eating it like a zoni vegetable soup, or using it in takikomi gohan (rice cooked with various seasoning and ingredients). Currently, suggesting various recipes by using the manufacturer’s product is common, but at the time of the launch in the 60’s it was a new effort.

These efforts proved successful. Matsutake-flavored clear soup became a solid favorite as a clear soup that enabled consumers to enjoy the exclusive image and the rich aroma of matsutake mushrooms.

Asage (breakfast) reversed the poor image of “instant products.”

At that time, most instant foods were considered cheap and tasteless.

To counter this image, Nagatanien set out to develop a high-grade instant miso soup that tasted as good as the homemade version.

Nagatanien sought to create a high-class feel for the product, from the miso and the chunky ingredients in the soup right through to the packaging.

Most instant miso soups at the time were made using hot-air drying. Hot-air drying was cheap but it left the ingredients with an unpleasant dry smell and ash-like quality, and a taste that was far inferior to fresh miso. Nagatanien decided to use the freeze-drying method, which, while expensive, maintained crucial flavor. The company collected miso from all over the country and selected the one that was most suited to freeze-drying.

For the chunky ingredients in the soup, Nagatanien used high-quality itafu baked wheat gluten sheets from the Shonai region, seaweed with superior color and taste, and freeze-dried green onions. The company was also extremely selective when it came to the katsuobushi dried bonito flakes, crucial to the flavor of the miso soup.

In terms of packaging, Nagatanien selected from hundreds of candidates a design with a high-class feel and a perfect combination of warm collage and strong calligraphy characters. As for the name, Nagatanien chose the ancient word for breakfast, Asage.

Will people pay four times the regular price?

Asage was an instant miso soup made from an abundance of high-quality, high-cost ingredients. On top of that, the oil shock had sparked rapid inflation and cost prices were rising before your very eyes. Finally, Nagatanien settled on a price for Asage of 40 yen per sachet (4 sachets for 160 yen). That was four times the amount charged for regular instant miso soup. Asage was launched in February 1974 amid doubts that such an expensive product would ever be embraced by consumers.

Despite these concerns, Asage generated strong sales. The product’s comical TV commercial featuring master of rakugo, Japanese comic storytelling, Yanagiya Kosan, and a girl was hugely popular. Just as Yanagiya Kosan exclaims in surprise, “Is this really instant?” a consumer survey revealed people also felt Asage instant miso soup was tastier than the miso soup they made at home.

Nagatanien followed up the Asage hit product with the launch of Yu-ge (evening meal) in June 1975 and Hiruge (midday meal) in February 1976, fueling a boom in the miso soup market.

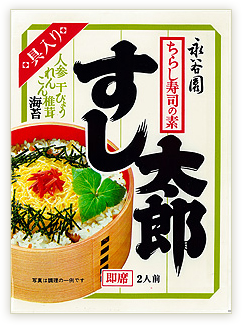

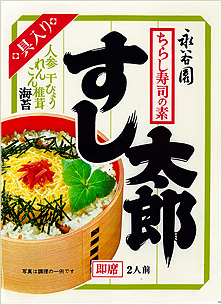

The launch of Nagatanien’s first wet goods: Sushitaro (an instant mix for Chirashizushi, a form of sushi consisting of rice topped with a variety of raw fish and vegetables or garnishes.)

In 1976, the three most popular menus among children were curry, hamburgers, and sushi. Nagatanien decided to focus on sushi and formed a new product development project team.

Project members met five or six times a month to formulate ideas based around the concept of being able to eat sushi whenever you want to.

This was Nagatanien’s first foray into the field of wet goods, so the project team tested and retested other company’s products and came up with the idea of making sushi which was quick and easy to prepare.

Four months later, the idea of Sushitaro one sachet per serving was emerged. Developing the idea was one thing, but manufacturing Sushitaro was another thing, as it was the first wet good product for Nagatanien. The machinery was not able to accurately distribute uniform amounts of carrots, mushrooms, lotus root, and gourd into each sachet. Thus, the factory had to adopt a laborious process of measuring the ingredients into individual tea strainers and spooning then into the sachets by hand. It was tough for a while, but, after much trial and error, the problem was resolved by reducing the amount of sweet vinegar and reconsideration of better way to combine the ingredients.

Sushitaro was launched roughly one year after forming the new product development team. It was to become one of Nagatanien’s best hit products.

The quest of a wandering researcher is to discover a world-first taste!!

The launch of Mabo Harusame

Employee A returned from two years of “study” as a drifting researcher with a hint for a new product. What was it? The story unfolds!

During his travels, employee A visited a certain restaurant where he came across a regular Chinese soup. He thought to himself, “This soup is really tasty. It is thick and rich and would probably go really well with rice!” But his long experience as a wandering researcher helped him connect the Chinese soup with something slightly more unusual.

That thing was harusame or bean-starch vermicelli.

Employee A thought he could create a completely new product by combining Chinese soup and bean-starch vermicelli. This was the taste he had been looking for.

Employee A rushed back to Japan and straight away began researching how to commercialize his idea. The result was Mabo Harusame, a spicy Sichuan minced meat and bean-starch vermicelli dish. Today, we consider this to be a typical Chinese dish but, in fact, it was not known anywhere in the world until that day.

The company considered employee A’s idea a good one, so everyone cooperated to commercialize the idea swiftly.

As a result, in November 1981, two years after introducing the “wandering employee system,” a Chinese dish created in Japan, Mabo Harusame, was launched. The product, and the mabo harusame dish itself, became well-known throughout Japan.

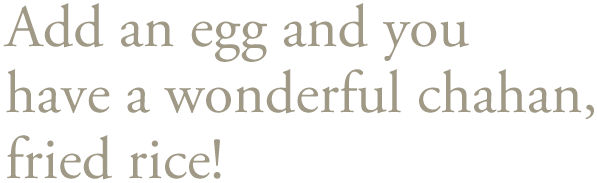

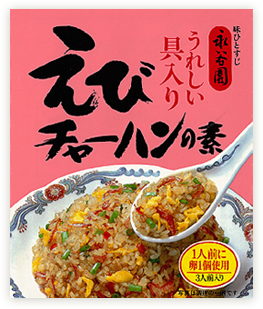

Add an egg and you have a wonderful chahan, fried rice!

Chahan no Moto fried rice seasoning with mixed filling became a big hit.

The Chahan no Moto fried rice seasoning market at the time was dominated by powder seasoning with no chunky filling.

Nagatanien determined to develop satisfying fried rice full of chunky ingredients that could be made quickly and easily at home.

For the generous chunky mixed ingredients, Nagatanien first considered a variety of wet ingredients. However, following repeated testing, the development team realized that what made fried rice taste so good was not the chunky ingredients but the loose, crumbly feel of the rice and the savory taste of the cooked egg.

After much trial and error, the team finally hit on the idea of creating a powdered seasoning with added chunky ingredients, and getting people to add an egg at home. There were several advantages to deciding on a powdered seasoning: Powdered seasoning successfully absorbed the moisture from the rice to achieve the crumbly, dry feel, and Nagatanien could apply its long experience and expertise in creating delicious dry goods.

Nagatanien also developed creative packaging, designing an attractive mound of on a round plate and including a Chinese spoon which was about to be brought into one’s month to express the product’s delicious taste and added originality. These touches have now become second nature in the industry, but it was Nagatanien who first introduced them.

When Chahan no Moto seasoning was in development, the fried rice seasoning market was small and the company didn’t expect it to become a hit product. However, having introduced the idea to consumers, sales of Chahan no Moto, fried rice seasoning increased favorably, and it eventually became a big hit boasting sales twice or even three times the size of the original market. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Chahan no Moto with added chunky filling carved an entirely new market.

Nagatanien’s quest for originality is probably the biggest contributing factor to its huge success and ability to fulfill latent customer needs that are not being satisfied by existing products.

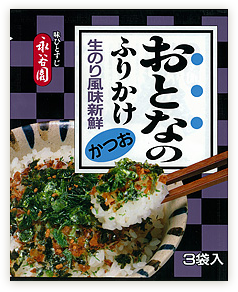

Otona no Furikake (Furikake for Adults/ seasoned topping for rice) makes its debut, popular with adults and kids alike

Challenging the preconception that furikake is for kids

As manufacturers competed ruthlessly in the furikake market, Nagatanien was always conducting tireless research to create a new hit product.

When reviewing the consumer data, the manager in charge noticed something interesting.

Furikake was popular with children and nearly 100% of children up to the age of 11 ate furikake, but demand dipped sharply among elder children and young adults from 12 upwards. The data showed clear evidence that consumers thought furikake was for kids. In view of the declining birthrate, that spelt danger for future furikake sales.

The manager became convinced that, to expand the furikake market, it was vital to squash the preconceived idea that furikake was a kid’s product, and set about launching a project to create a furikake that not only satisfied kids but adults as well.

Clever materials, packaging and commercials

The team explored what makes furikake that satisfies adults from every possible perspective.

They worked hard to preserve the vivid bright color and unique taste of the nori seaweed. In terms of the packaging, they decided on a high-class feel with a large blank white space to write “Otona no Furikake” in black writing.

For the TV commercial, the team challenged the new technique of getting a child to play the main role and view the adult world through a child’s eyes. The TV commercial was a great success, and Otona no Furikake became well known.

A long-term best seller supported by consumers of all ages.

In October 1989, the company released three new flavors of Otona no Furikake, bonito flakes, salmon, and Japanese wasabi mustard, in specific regions. Local stores witnessed bumper sales of sample foods, with some people buying two or three packages each, boosting sales far beyond those of the previous product. In February 1990, the product was launched nationwide with sales far exceeding expectations in every region.

An analysis of the data shows that Otona no Furikake is as popular with consumers of all ages from 5 to 55, and as popular with male as with female consumers. A true validation of the researcher’s firm belief that truly delicious products would be popular regardless of all ages, and gender